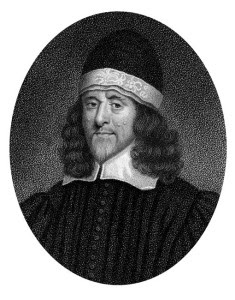

After spending the past year working through the collected works of Thomas Goodwin, one treatise which particularly caught my attention was The Heart of Christ Toward Sinners. I know that I am not alone- it is one of Goodwin’s pieces which made the cut into the Puritan Paperbacks series, and Dane Ortlund’s Gentle and Lowly includes an entire chapter which reflects on the same. It is one of Goodwin’s most recognized works, and for good reason.

So often, when we look to Jesus in the Scriptures, we often impose on his personality our theological preferences. Some Christians, protective of justification, think Jesus approached every situation as a sort of trial lawyer. Others see him as an overwhelming source of love toward others, and that his love guided his interactions. One might even read the description of Jesus as a “man of sorrows” (Isa. 53:3) and see him as a melancholy servant, simply obeying the eternal decree of the Father.

Even so, the divinity (God-ness) and humanity (human-ness) of Christ means that he experiences every emotion we know ourselves. And that includes, to my great relief, happiness. The source of all joy and happiness, it turns out, was happy himself.

So what actually made Jesus happy? What were the things that made the God-man laugh and rejoice? And, in a moment of honesty with ourselves, can we be happy with the same?

Biblical Evidence

The gospels have many references to the word “joy.” People respond with joy at certain circumstances, such as when the wise men find the guiding star to the newborn King (Matt. 2:10), and Zaccheus comes down from the sycamore tree “and received [Jesus] joyfully” (Luke 19:6). The seventy-two disciples react with great joy when they returned to Jesus and reported that demons are subject to the name of Christ (Luke 10:17). Jesus himself even refers to joy in the parables, such as when the good and faithful servant enters into the joy of his master (Matt. 25:21-23).

But when narrowing in on a joy which belongs to Jesus, we see two clear examples, both of which come in Jesus’ final words to the gathered disciples. Our first comes in John 15:1-10. In the preceding verses, Jesus has just called himself the true vine, the only means by which we can maintain a proper relationship with the Father. The Father is glorified under certain conditions- if we abide in Jesus, and his Words abide in us. Jesus tells his disciples this for a specific purpose; “That my joy may be in you, and that your joy may be full” (John 15:11). What makes Jesus joyful in this context is when God’s Word abides in us, we abide in Christ, bear much fruit, and God is glorified as a result.

The second location comes just two chapters later, where Jesus has entered into the high priestly prayer. Jesus is asking his Father to care for his disciples after his imminent death and ascension. In this passage, Jesus establishes a pattern, showing that things ascribed to the disciples are done much greater by himself. The Son glorifies the Father; therefore, the disciples should glorify the Son (v. 10). The Son has received a word from the Father, and so have the disciples (v. 8) Just a few verses earlier, Jesus establishes a pattern- the Father is glorified in the Son, and the Son is glorified in his disciples (17:10). The Son has joy, and he hopes that the same is fulfilled in the disciples (v. 13).

It is important to notice that this joy is not somehow dependent upon the disciples, or responsive to other conditions. “That they may have my joy” makes clear that there is an already existent joy in Jesus’ heart. Given the context of the previous 12 verses, it is clear that Christ’s joy is intimately and deeply tied to those moments when the Father is glorified, known, and believed. The joy of John 15 is more related to the disciples, while that of John 17 is more related to the Father. In other words, Jesus’ joy in the former is looking downward, while his joy in the latter is looking upward.

Goodwin on Christ’s Joy

Thomas Goodwin, in Volume 4 of his Collected Works, likewise sees the importance of Jesus calling it “my joy.” When the Lord says that he desires for his joy to remain in the disciples, it implies an overwhelming reality; “When Christ says, ‘that my joy may remain in you,’ it implies that even in heaven, he will have reason to rejoice in them when he hears of their unity, love for one another, and obedience to his commandments” (PAGENEEDED). Goodwin reminds us that the joy of Christ is both eternal and immediate, at the same time. It is local and omnipresent, in the individual follower of Jesus as well as ever present in the everywhere God.

Goodwin is astutely aware of the fact that this dual joy- both in the believer and in Christ, shared among each other, is a powerful motivator to encouragement. So often, when our joy is based upon our immediate surroundings, it is difficult to see or understand anything else than our own trials and travails. Much Enlightenment philosophy worked to hammer this point home- we cannot trust anything beyond our natural existence, so whatever the material world offers us is our lot in life. But looking at the world through a Christian lens offers something profoundly different.

After looking to the cross for our salvation, we have an opportunity to rise and look elsewhere for our joy. Instead of looking to our left and right and finding ourselves in how others see us, we have joy in the One who calls us his own. When the pressure comes to find joy in accomplishment, we remind ourselves of the joyful fact that the only accomplishment that matters. Goodwin himself notices as much:

Look at how Paul expresses himself in 1 Thessalonians 2:19, saying, “What is our hope or joy or crown of rejoicing? You are our glory and joy.” John says something similar in 3 John 1:3, as he greatly rejoices upon hearing the good testimony about Gaius. He declares, “I have no greater joy than to hear that my children walk in the truth.” Now, what were Paul and John but instruments through whom others believed and were brought forth? They were not the ones crucified for them, nor were these individuals their own offspring. Therefore, if Paul and John find immense joy and satisfaction in the well-being and faithfulness of those they have ministered to, how much more so must it be for Christ, whose connection and care for us is infinitely greater?

His joy is our joy.

Does It Make a Difference?

Writing on the topic of joy seems counterintuitive to someone like myself. I could blame it on the PTSD diagnosis from the Army, or perhaps the interpersonal difficulties I’ve faced in local church bodies over the years, but the truth is more pervasive- depression and a lack of joy have been a feature of my life for many years, not a bug in the system.

But if my savior has joy, then I cannot give up looking for the same. The world offers glimpses- the love of a wonderful wife, the delightful exuberance of young children, or the vast incredulity I feel when exploring nature. But if I hope to see a happiness that lasts for eternity, it only makes sense to look to my Savior and see what makes him joyful. It’s the glorification of the Father, and seeing others come to do the same. It is the magnification of love that both created us, died for us, and raised us up to eternal life.

Is joy easy? By no means. But is joy worth seeking? By all means.

Leave a comment